The Fierce Nonviolence Pilgrimage

September 2025

by Fumi

Not every journey is a pilgrimage. Sometimes we travel for recreation, other times for business, still other times to visit friends and family. So, when 18 of us gathered in Spokane, WA, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing and begin an 11-day journey across nuclear-impacted communities in Washington state, what, exactly, made it a pilgrimage?

In Mystics and Zen Masters, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton writes, “The geographic pilgrimage is the symbolic acting out of an inner journey.” A crucial element of pilgrimage, then, is the way we attune to that inner journey, and open ourselves to the possibility of transformation.

Pilgrimage participants pray for peace in front of the Trident submarine base.

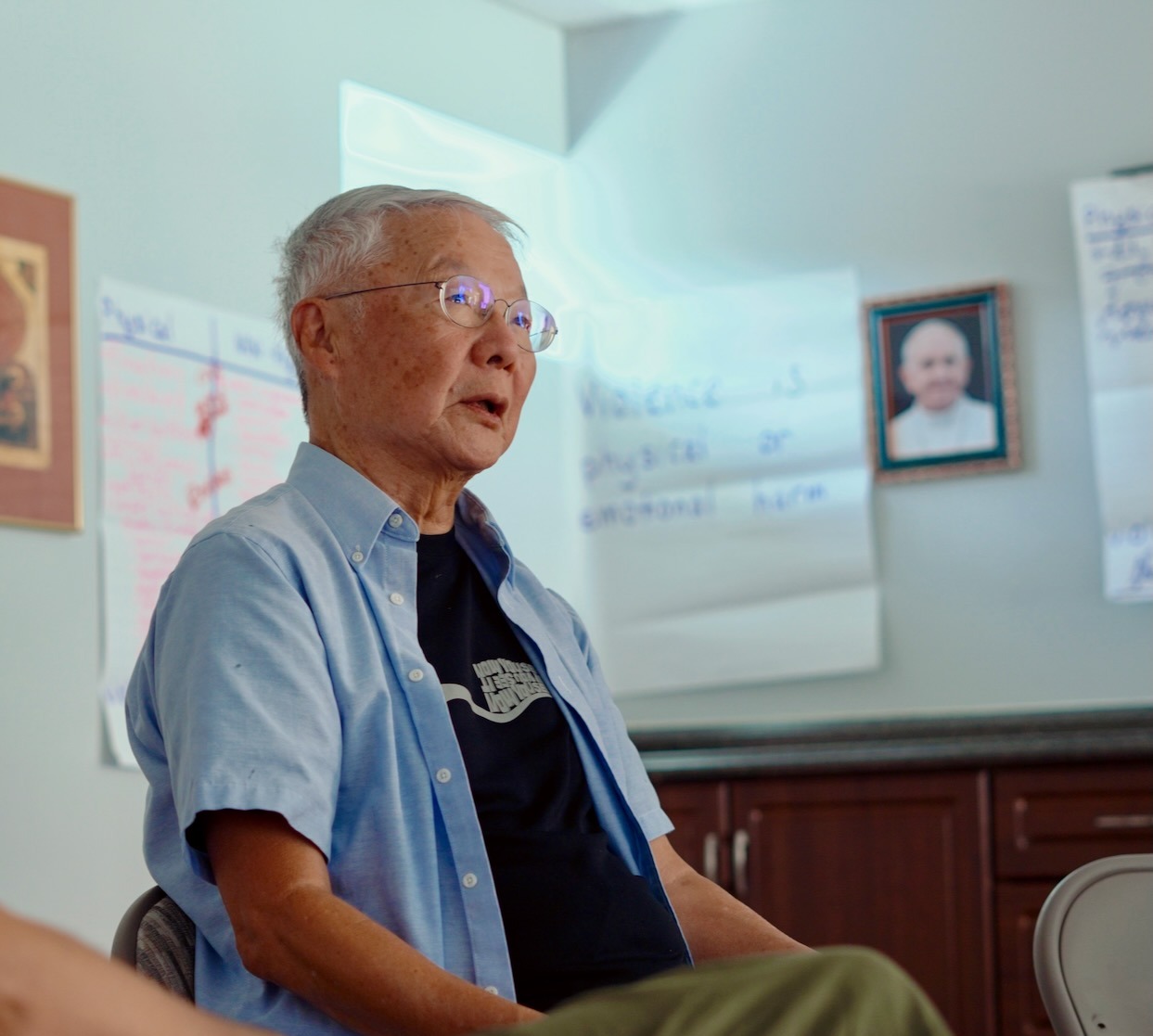

Our journey took us to communities impacted by nuclear weapons at every stage of their life-cycle: we heard from the Spokane nation about the impacts of uranium mining on their reservation; from the Yakama nation about the production of plutonium and disposal of nuclear waste at the Hanford site; from the Marshallese community about the devastating effects of above-ground nuclear testing (the United States detonated 67 nuclear bombs over their land and sea over a span of 12 years); and from my father, a survivor of the Hiroshima bombing 80 years ago.

Our journey ended at U.S. Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor on the Hood Canal, the site of the largest concentration of deployed nuclear weapons in the United States. As Josie Yaconelli, one of our participants, said, “Most pilgrimages are marching towards the light, toward enlightenment, toward a place that is sacred and holy and good. And we are marching toward death.” Indeed, Bangor is home to 8 of the United States’ 14 Trident submarines, each of which has the capacity to destroy the earth and all living beings.

“Most pilgrimages are marching towards the light, toward enlightenment. And we are marching toward death.”

What was the inner journey that paralleled this geographic march to death? There are, undoubtedly, as many answers as there were participants on this pilgrimage. Each of us wrestled in our own way with the reality of pain and suffering in our midst. Here, too, we learned from our hosts: “We are moving from grief to healing,” said Spokane activist Twa-Le Abrahamson, as she described the canoe journeys her people have been taking as a way of reclaiming the waterways and their traditional ways of living and building community.

Norimitsu Tosu shares his family’s experience of the Hiroshima bombing.

We did our best to support one another in the difficult task of facing all that is real of death and destruction without giving into despair. We rooted our days in song, silence, storytelling, and ritual, experimenting with how to cultivate depth in our souls, individually and collectively, in the face of the seemingly insurmountable forces besieging us.

Of course, there was also laughter and levity, a campfire, dancing, and a “No Talent Show” in which every participant performed a non-talent (rolling across the stage won first place) – these, too, were medicines for the journey. Finally, there was community – the imperfect, tension-filled, but in the end loving group of young adults who took a risk, and stayed engaged.

We wove into the journey a series of trainings on nonviolent social change, in order to give participants a way to act in response to the stories we heard and the experiences we had. The answers to our problems are not always clear, but we hope that having the framework to understand that satyagraha involves at least three things – direct action to get in the way of immediate injustice, a constructive program to build the world we long for, and spiritual practice for inner transformation – helps the young adults experiment with their lives as they grope for ways to build peace.

We wove into the journey a series of trainings on nonviolent social change, in order to give participants a way to act in response to the stories we heard and the experiences we had. The answers to our problems are not always clear, but we hope that having the framework to understand that satyagraha involves at least three things – direct action to get in the way of immediate injustice, a constructive program to build the world we long for, and spiritual practice for inner transformation – helps the young adults experiment with their lives as they grope for ways to build peace.